by Phil Egan for The Sarnia Journal

(2016) For weeks the wretched stink pervaded both Sarnia and Port Huron.

It was the main topic of conversation, and newspapers on both sides of the border complained about the smell and speculated when it would end.

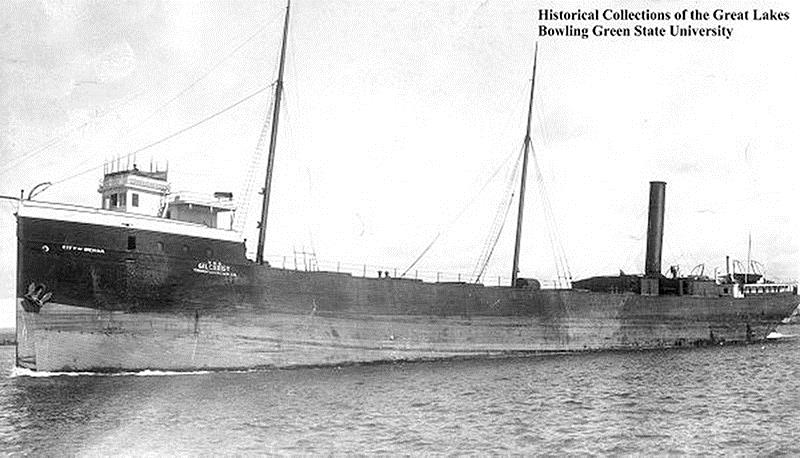

It was an embarrassing end for a once-proud vessel.

The ghastly odour came from fermenting grain laid out to dry beside the waterfront on the property of the Reid Wrecking Company. The story of how it got there takes us to the foggy morning hours of Aug. 26, 1911.

Captain George T. Inman was at the helm of the City of Genoa. The grain freighter had left Lake Huron and passed into the St. Clair River when the fog closed in. In her hold lay 125,000 bushels of wheat and corn.

Blinded by the fog in the narrow straight, Inman edged his ship closer to the Canadian shore and dropped anchor at 4 a.m. It would be safer, Inman felt on that Saturday morning, to wait for the sun to rise and dissipate the fog.

Sunrise came at 5:46 a.m. to reveal a chaotic scene. At about 5 a.m. Captain C.C. Hanley, heading downriver, drove the freighter W.H. Gilbert directly into the bow of the City of Genoa, which had been turned by the current to face upstream.

Pandemonium ensued as sailors aboard the rapidly sinking ship raced above decks. Just 100 feet from shore, she settled to the bottom, her decks awash. Only the pilothouse and smokestack remained visible in the water.

The Gilbert, with a barge in tow, laboriously turned about in the strong river current and rescued the crew of the sinking ship.

For weeks, the crippled City of Genoa lay in the river. Finally, the salvager Tom Reid of Sarnia built a cofferdam around her hull and raised the wreck. She was judged too badly damaged to be saved, but an effort was made to salvage the water-soaked and already fermenting cargo. Laid out on the riverbank, its putrid smell was a tangible reminder of the ignominious fate of the once proud, 19-year-old City of Genoa.

It wasn’t until Oct. 9, 1915 that the City of Genoa finally received her funeral pyre. Her boiler and engines were removed and she was set ablaze. Later, the blackened hull was towed into Lake Huron and sunk.

Her remains lie there to this day; together with countless other lost ships – some say as many as 4,000 submerged below the surface of the Great Lakes.