Phil Egan, special to The Sarnia Journal

(2016) If you were fortunate enough to live in Sarnia during the First World War there were jobs galore at Mueller Brass.

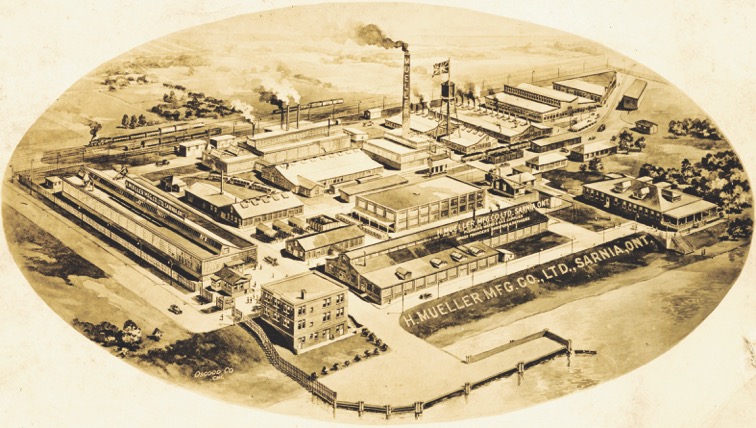

Lured here in 1912 by Mayor Joseph Dagan with a $30,000 bonus, Mueller Brass opened modestly with 22 employees. They worked a 50-hour week manufacturing bronze and brass fittings for plumbing and water companies.

Mueller’s presence in Sarnia was part of a plan by Dagan, first as an alderman and later as mayor, to drive the city’s population above the 10,000 mark, the magic number needed to gain the benefits of city status.

Mueller’s promise to ultimately hire 75 employees led to city status on May 7, 1914 with the visit by the Governor-General, the Duke of Connaught and Princess Patricia.

When the fighting broke out that summer Mueller Brass quickly shifted to war production, building shell casings and other brass forgings for Canada’s rapidly growing war machine. Two years later Mueller had become one of Sarnia’s largest industries, with 1,800 workers.

They toiled in three shifts, 24 hours a day – but it still wasn’t enough to meet the voracious war appetite for munitions.

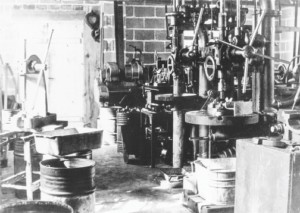

An undated interior view of a brass finishing shop at the Mueller Manufacturing Company.

Photograph courtesy, Lambton Heritage Museum, Grand Bend. JA.6c.mu.5.6.

In an “Appeal to Sarnia Citizens” issued on April 13, 1918 and carried in the Sarnia Canadian Observer, the company cried out for help.

“We have tried every conceivable avenue through which we might obtain men and women to work in our Munitions plant in Sarnia,” the message began.

The Imperial Munitions Board, it explained, was appealing to Mueller on a daily basis for greater production. Despite running the plant around the clock it was extremely short-handed, and able to place “dozens of men and women at pleasant tasks for which they will be well paid.”

Well paid, in 1918, meant 30 cents an hour plus a weekly $3 bonus.

Desperate to find manpower, Mueller felt it had no choice but to appeal to the people of Sarnia’s “Patriotic Pride” for assistance “in the greatest measure possible.”

“We ask this favour of the citizens of Sarnia,” the company added, “because we believe that, next to the duty that we owe our Government in this time of stress, we owe the citizens of Lambton County the preference in giving them positions with our company.”

The message was clear. Give us workers, or we’ll bring them in from elsewhere.

“It is impossible,” the appeal concluded, “for us to do more than we are now doing, and that is not enough.”

It appeared to work. By war’s end, Mueller Brass had sales of more than $7 million annually and its overseas business share was 90%.