Phil Egan

It is a fascinating artifact of the final days of the Great War.

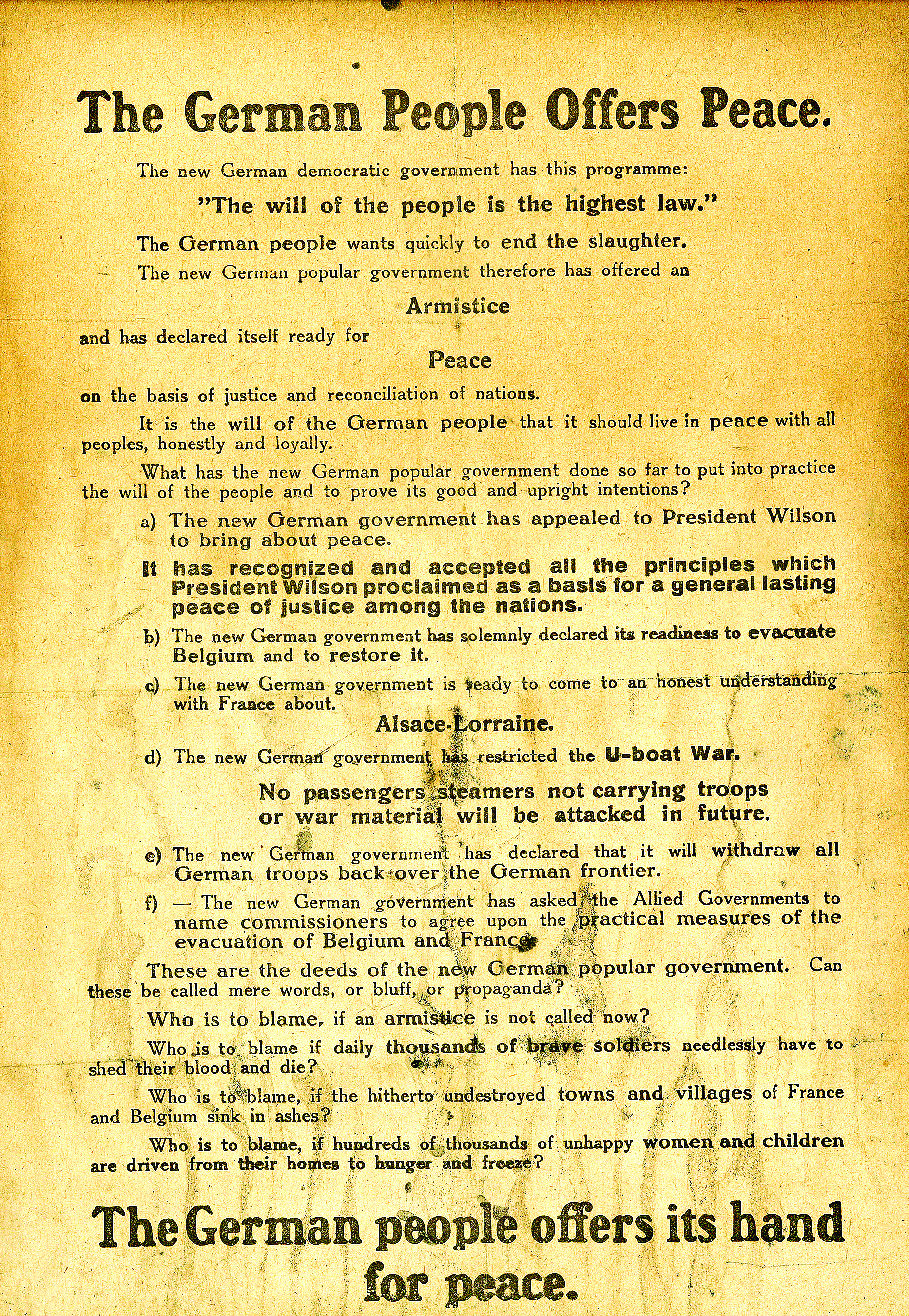

A Journal reader recently shared it with the Sarnia Historical Society. Encased in glass to prevent further deterioration, the yellowed leaflet is written in English on one side and French on the other.

Proclaiming to come from the “new German democratic government, it is a plaintive plea for peace.

As early as August of 1918, Germany knew the war had been lost. That spring and summer, German forces had been repelled in five major offensives. The Reich’s manpower was nearing exhaustion.

Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917 had brought America into the war, and U.S. soldiers were now arriving on the western front in force.

By Aug. 8, Canadian forces had begun their now-legendary 100 Days Offensive that pushed back German forces in a series of battles. These included the Battle of Amiens, the Second Battle of the Somme, the Battles of the Scarpe, the Canal du Nord, Cambrai, the Selle, Valenciennes, and, finally, at Mons on the final day of conflict before the Nov. 11 Armistice.

With Germany crumbling, desertions mounting and enthusiasm for war gone, the leaflet was part of a German plea to negotiate terms other than unconditional surrender.

“The German people want quickly to end the slaughter,” the leaflet declares. “The new popular German government” was offering “an Armistice, and had declared itself ready for peace on the basis of justice and reconciliation.”

Copies of the leaflet were placed in the path of advancing Allied armies, explaining, “the new German government has appealed to President Wilson to bring about peace.”

The leaflet claimed Germany’s intent “to evacuate Belgium and to restore it,” and pledged “to come to an honest understanding with France about Alsace-Lorraine.”

Alsace-Lorraine had belonged to France since the 18th century. France had been forced to relinquish the territory to the new German empire after losing the Franco-Prussian war.

Now, Germany was, belatedly and cynically, trying to offer it back as part of a negotiated peace deal.

As a sop to the Americans, the leaflet states that, “the new German government has restricted the U-boat war.” There would be no more attacks on passenger ships “not carrying troops or war materials.”

Finally, the leaflet tries to “close the deal.”

“”Who is to blame,” it asks, “if an Armistice is not called now?”

“Who is to blame if, daily, thousands of brave soldiers have to shed their blood and die?”

“Who is to blame if the undestroyed towns and villages of France and Belgium sink in ashes?”

It was a cry of desperation and propaganda that was ignored by the conquering Allied forces.