by Paul Morden for the Sarnia Observer

(2014) If it weren’t for an American-born engineer who earned the nickname “minister of everything” during his long career in Canadian politics, Sarnia might never have become home to the country’s Chemical Valley.

Chosen by Prime Minister Mackenzie King to lead efforts to supply Canada’s war machine, C.D. Howe drove the effort to replace supplies of natural rubber, cut off by the start of the Second World War, by building a plant in Sarnia to make synthetic rubber using still largely experimental technology.

Sarnia was chosen because its Imperial Oil refinery could supply some of the chemicals needed, and the rest could arrive by ship to the plant site on the St. Clair River. At $50 million, the rubber plant was the Canadian government’s largest single expenditure during the war, said Matthew Bellamy, a Carleton University professor who wrote the book Profiting the Crown, about the Polymer Corporation.

“C.D. Howe is central to all this because he’s the one who had the guts, the strength to go ahead when it needs to be done,” Bellamy said.

It was a risky proposition since synthetic rubber hadn’t actually been created yet outside of a laboratory, and what was named the Polymer project faced a looming deadline to begin production before the country’s stockpile of natural rubber ran out.

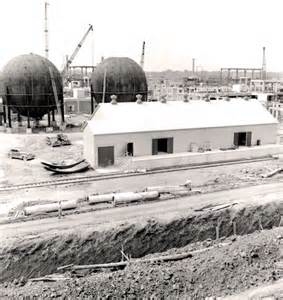

The plant site covered eight city blocks, and its first unit went into production in the fall of 1943, just 13 months after construction began. “It’s a colossal feat,” Bellamy said. “They find the workers, they find the raw materials, somehow, and they get it up and running to keep us in the war.”

Once peace arrived a few years later, it was Howe who decided to keep Polymer operating as a Crown corporation, with the aim of making Sarnia the centre of a new Canadian chemical industry.

At the time, Polymer itself had 2,000 workers, and companies like Dow Chemical and Fiberglas (Canada), followed by others, began setting up shop in the community. Because of that, Sarnia boomed in the postwar years, doubling its population and tripling its industrial output between 1945 and 1955, Bellamy said.

Polymer became a successful international company and set up research facilities in Sarnia where it remained based. “In the 1960s, Sarnia had more PhDs per capita than anywhere else in Canada,” Bellamy said. Instead of an outward brain drain, Canada was attracting scientists from the U.S. and Germany because of Polymer during that era, he said. Bellamy said Polymer veterans he spoke to while researching the book told him Sarnia was a much different place during the 1960s and early 1970s, before it began its transition into a more blue- collar town.

During the 1970s era of economical nationalism in Canada, Polymer was sold to the newly created Canada Development Corporation and later renamed Polysar. But, after Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and the Conservatives came to power, Polysar was sold off to Nova Corporation and the rubber division ended up being sold, ironically enough considering its birth during the war, to German-owned Bayer AG. Bayer still operates a rubber plant on the Sarnia site under the Lanxess name.

In the years that followed the sale of Polysar, other changes were happening in the economy and the petrochemical industry. As a result, Chemical Valley’s workforce shrank significantly and several of its plants closed down.

The boom, just like Polymer, was gone.